He will tell you that himself.

He’s a bad copy of a Marlboro Man.

His Just For Men dark hair rolls back over his scalp in a greasy wave.

A shoe polish bread.

Skin like beef jerky.

He rides around the streets of SLC on his three-wheeled bike. He is always shirtless, in a fishing vest left open and camo cargo pants. He used to wear combat boots, but he switched to slippers at some unmarked point.

Everyone knows Mickie.

To me, he looks like someone accidentally left behind. Someone who staggered out onto the streets after a couple of decades. Decades of what I don't know— war, drugs, the bottom of too many glass bottles.

We’re comfortable with Mickie. Although we have had some close calls. I try my best not to run him over. He's like a stray cat, constantly darting out into the road when you least expect him to.

Then one day, Mickie rolled up to talk to the Talented Mr. Ries in the driveway. There was something wrong with his leg, so I was called outside to consult. What I found was that Mickie’s leg was gangrenous from the midcalf down, hence the slippers.

Enter two LDS missionaries strolling up the block, trying to collect any loose souls among the brick houses of the polygamist and the poor.

And there we were, Mickie the millionaire on his tricycle, the Talented Mr. Ries, myself the un-doctor, and two young warriors of God’s army. Intervention-style we began giving Mickie his choices, go to the clinic now or lose the leg.

It wasn't as easy as you would think. Mickie didn't want anything to do with going to the doctor. Had I been enjoying any part of being so close to medicine again, it was ripped away by Mickie, the millionaire's last objection, "I don't have any money."

The system "can't" know how bad it is down on the front lines. The barriers to seeking treatment when someone like Mickie, who is vulnerable and in pain, sees noway up from where he is, are simply too Goddamn high. As he saw it, his choice was to go from wearing boots to slippers while his leg rotted away.

And as men in suits argue about healthcare, they have no idea the damage they are doing. They go to church on Sunday, and on Monday, they turn around and block the bodily salvation for the people ‘beneath’ them.

Inaction has the same ethical price tag as action. Failure to provide access and blocking it are the same thing.

These days when I run, I run the river trail north. It takes me to the doorstep of the homeless I wrote about in the article that granted me high praise and a label: Social justice advocate.

Daniel, the man I interviewed, still lives there, hiding inside the banks of tall golden grasses.

Nothing has changed for any of us.

Sometimes Daniel smiles at me, and I smile back. Most of the time, we pretend not to know one another while I try not to notice the woman he was with when I interviewed him is gone, and another is in her place. I’m just another broken hope, like a ghost skirting the edges of the issue.

The difference between Daniel and Mickie and myself is uncomfortably slim. Daniel lives down the street in a tent by the river, Mickie lives down the road behind Brent's house in a trailer, and I live in a little white house.

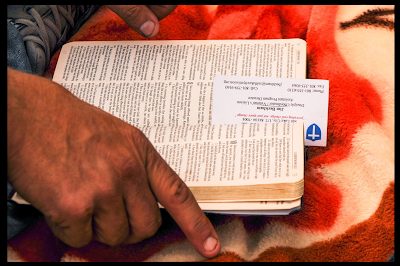

Of the three of us, I have the loosest soul. Daniel carries a bible, and Mickie claims the LDS faith. I believe in absolutely nothing and have faith in even less.

I’ve been in Mickie's slippers; my sister died in them. Plain sight is a horrible place to suffer alone. How can things change when we are all so willfully blind to each other's needs?

In the end, I told Mickie, "You can go with the Talented Mr. Ries, or you can go to God, but only one of them is looking out for you right now."

And so there we all were, the Talented Mr. Ries, the broke Quaker from New England paying Mickie the Millionaire's medical bills, the two young missionaries walking off empty-handed, and me, the un-doctor left standing on the sidewalk.

~We all want something beautiful, man I wish I was beautiful... ~ Counting Crows

.JPG)